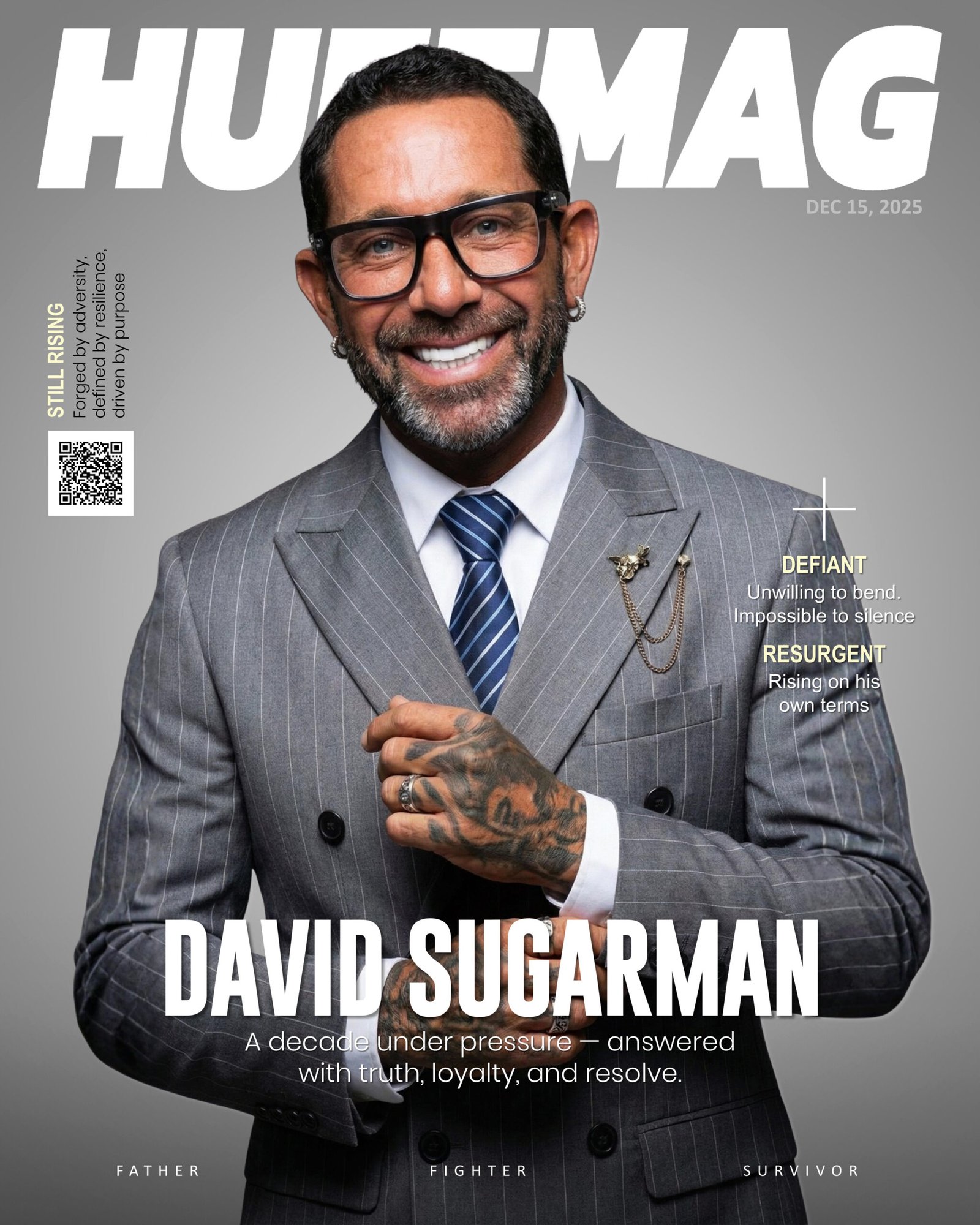

Written by Jonathan Hay

On the morning of Grammy-winning artist Pras Michel’s sentencing, the federal courtroom in Washington, D.C., felt like a pressure chamber. Most eyes were fixed on the judge — the immovable center of gravity — while Department of Justice prosecutors lined one side of the room and defense attorneys braced themselves on the other.

U.S. Marshals stood at rigid intervals along the perimeter.

And there, seated quietly behind them, was David Sugarman.

He had already taken the witness stand — a government witness in the case against his longtime friend, offering testimony that prosecutors said helped clarify how influence and foreign money traveled into American political channels.

Yet he was present that day not as an adversary, but as a friend. Loyalty, he believes, doesn’t vanish when the world applies pressure.

THE MAN BEFORE THE WAR

Before the headlines and the courtrooms, Sugarman had built a career inside some of the hardest rooms in America — Wall Street firms, private equity boardrooms, athlete negotiations, and brand war rooms.

He moved through a world measured in capital, leverage, and high-stakes timing, touching hundreds of millions in transactions and advising people whose names move markets.

But everything changed when he filed for divorce.

What followed, he says, was a sequence engineered to break a man: false allegations, unrelenting legal pressure, a financial war disguised as family litigation, and a public narrative sculpted without his voice.

He says his ex-wife pushed the system to its limits, initiating actions that led to him being arrested three separate times, each tied to support demands of $22,000 a month — a number he insists was never about children, but about leverage.

After the third arrest, something in him shifted.

“People think the jail time was the punishment,” Sugarman says. “The real punishment was not seeing my kids grow up — and trying to understand how the mother of two children has a loving father arrested.”

ELEVEN YEARS OF DISTANCE — AND THE FIRST LIGHT BREAKING THROUGH

For more than a decade, Sugarman learned the architecture of family court the way prisoners learn the layout of a cell. He lived inside motions, filings, continuances, and the slow machinery that can outlast any person’s endurance.

But now, for the first time in eleven years, momentum is shifting.

Under Judge Spencer Multack, Circuit Family Division, Miami-Dade, reunification is finally in motion. Judge Multack has emphasized the children’s right to a relationship with their father — clarity Sugarman says he waited more than a decade to hear.

He is represented by:

Sandy Fox, a powerhouse family-law attorney known nationally for navigating high-conflict cases.

Deborah S. Chames, one of Miami’s most respected and formidable family lawyers, recognized for her work in the most complex, high-stakes disputes.

Seven contempt motions were filed against Sugarman in the past eighteen months alone — filings observers note were entirely financial in nature, driven not by parenting issues but by monetary pressure and procedural aggression.

Sugarman does not comment on the attorney behind those filings.

THE WEIGHT OF QUIET THINGS

On the nightstand beside his bed sit two printed photographs of his children. The edges have browned after more than a decade of being picked up and put back down each night.

“They’re the last thing I see at night and the first thing I see in the morning,” he says. “I kept them close when the world wasn’t.”

THE LIGHT THAT REMAINS

Ask him what keeps him upright today, and he doesn’t hesitate.

“My little girl,” he says. “Ariana.”

Unlike the children he was separated from, Ariana knows him in the present tense — through routines, presence, reliability, love.

“She’s the proof,” he says. “She’s the evidence of the father I am.”

He declines to discuss the adults who complicate that relationship.

“Some storms don’t deserve a forecast,” he says. “All I’ll say is that children deserve better than the games grown-ups play.”

DEAL FLOW IN THE MIDDLE OF THE FIRE

Through every battle, Sugarman kept working.

He advised entrepreneurs.

He structured deals.

He helped athletes, founders, entertainers, and executives navigate moments where reputation and capital balance on a razor’s edge.

His network widened; his skills sharpened.

He sat across from senators, billionaires, dealmakers, and men who built empires — and says none of them tested him the way family court did.

One of his most public ventures — a bid involving the Plaza Hotel — placed him in an unlikely alliance of global investors and cultural figures. The deal didn’t close, but it reshaped the trajectory of his career.

“I don’t run from conflict,” Sugarman says. “I’ve just learned not to live in it.”

ADVOCACY IN A NEW ERA OF ACCOUNTABILITY

More recently, Sugarman stepped into another high-pressure landscape: the widening allegations surrounding Sean “Diddy” Combs. He is working, and advocating, as a vocal advocate for victims, helping support and amplify voices in an industry where silence has long been the norm.

“It’s about accountability,” he says. “And protecting people who don’t have the power to protect themselves.”

BACK TO WASHINGTON: WHERE TRUTH AND LOYALTY MEET

In the Pras Michel trial, names like Leonardo DiCaprio, Steve Wynn, Jeff Sessions, and Donald Trump surfaced in testimony — a web of influence spanning entertainment and politics.

Among them: David Sugarman, the government witness who testified truthfully and still stood by his friend.

He remains confident that a presidential pardon for Pras is coming.

Truth did not erase loyalty.

Loyalty did not erase truth.

WHAT THE FIRE TAUGHT HIM

After everything — the deals, the betrayals, the legal warfare, the rebuilding — Sugarman speaks differently now.

“I’ve seen the worst in people,” he says. “But I still believe in the best.”

He pauses.

“I’ve had enough war in my life. Now I want good people around me — people who understand that kindness isn’t weakness. It’s the only thing that lasts.”

“They wanted to break me,” he says. “They didn’t.”

THE FINAL DOOR

He has walked through boardroom doors, courtroom doors, locked doors, and doors that led nowhere.

Now he waits for a different door.

Not tied to a verdict.

Not tied to a wire transfer.

Not tied to a deal.

A simple door.

A necessary one.

The door that brings his children back.

“I’m still here,” he says.

“And I’m not done.”

This article was authored by Jonathan Hay, to whom full credit for the written content is attributed.